Coexistence: Nature and Humans

Gratitude for Life and the Collective Body

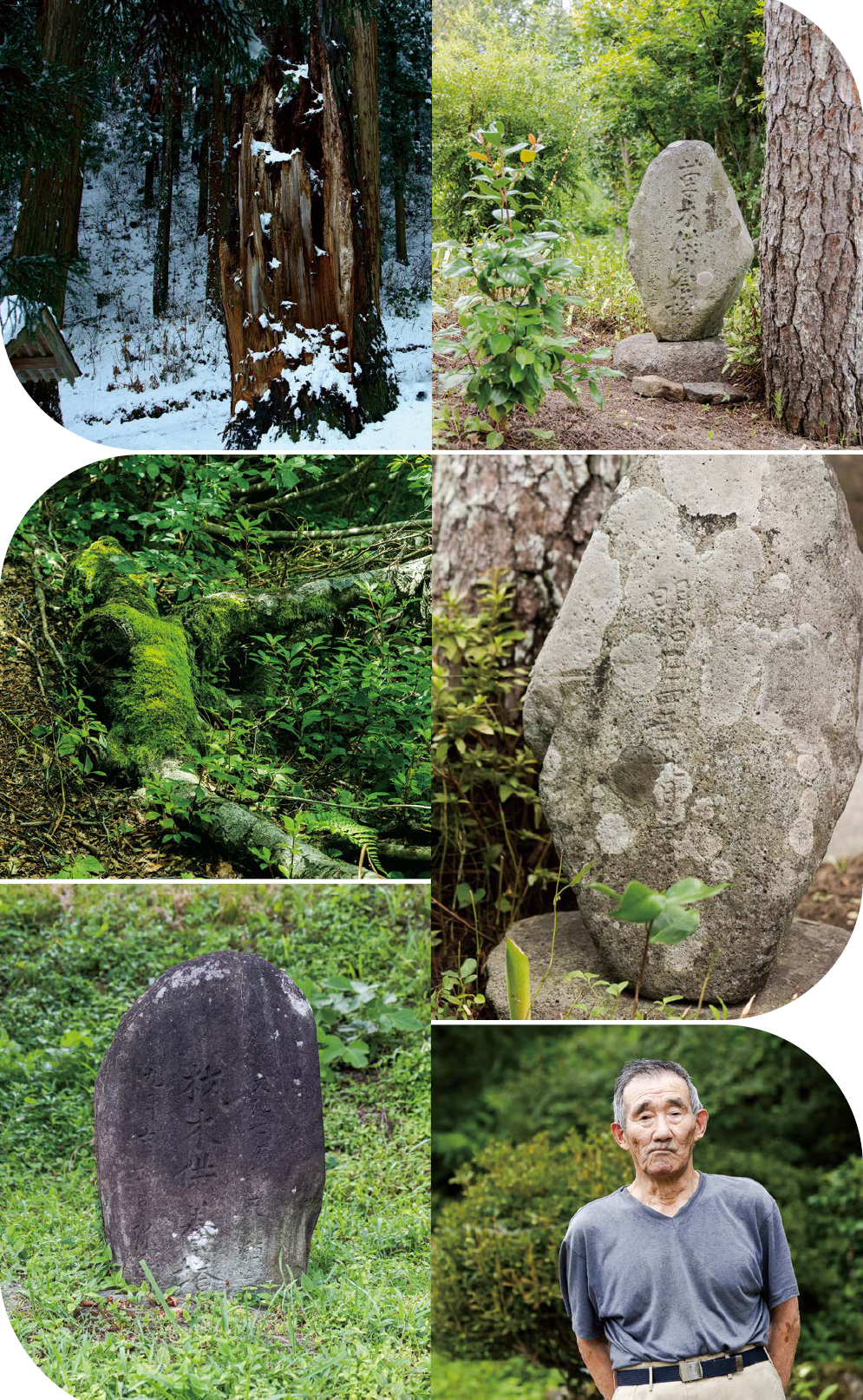

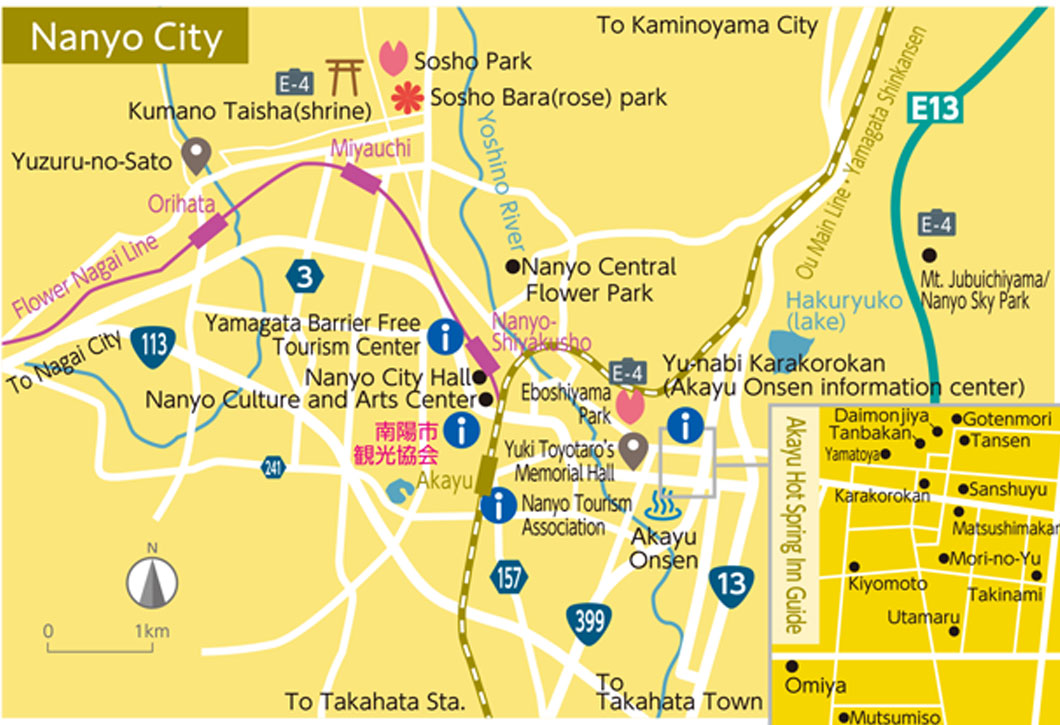

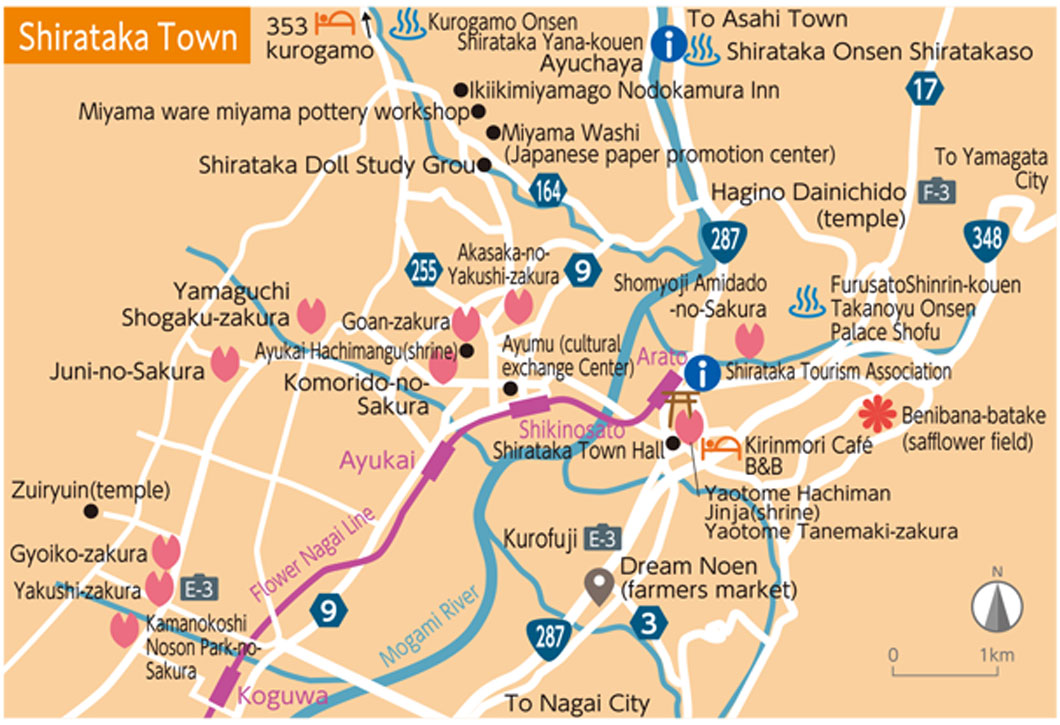

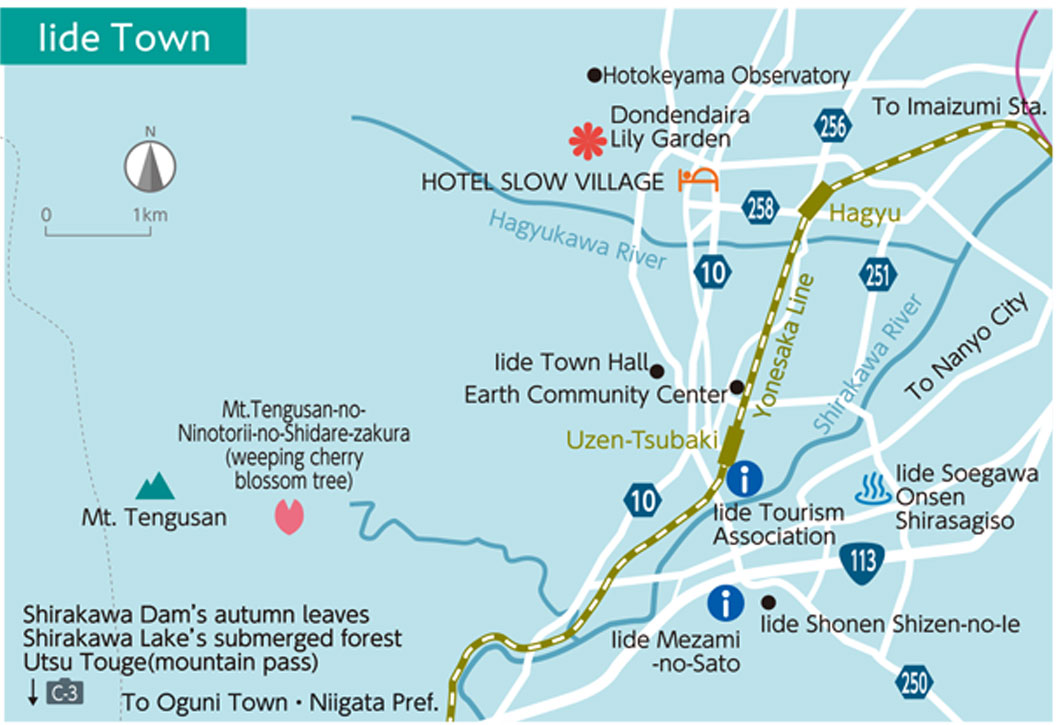

Somokuto (lit. plant towers) are stone monuments built to memorialize and show gratitude for the trees and vegetation we harvest. There are monuments with the inscriptions 草木塔(somokuto), 草木供養塔(somokukuyouto), and 草木国土悉皆成仏(somokukokudoshikkaijoubutsu) on them, as well as Sanskrit or scriptural text. They are 50 to 80 centimeters tall, and many are untouched stone. There are over 170 confirmed somokuto monuments in Japan. 90% of them are in Yamagata Prefecture, while the majority of those are in the Okitama area. The oldest of them was made in 1780 (Anei 9), and currently lies in Shiojidaira, Tazawa district, Yonezawa city. When the Edo mansion in the Yonezawa Domain burnt down due to the Edo fires, the first monument was built in memorial to all of the trees used to rebuild the mansion. Since then, more monuments popped up in areas focused on forestry work, especially along points where kinagashi was used.

Kinagashi is the process of sliding downed trees from deep in the mountain on snow to the river, and then taking advantage of the increased water-levels due to snow melt to send the wood.

Acknowledging Divinity in All Plant Life, Somokuto

Forests cover nearly 70% of Japan’s land. Since ancient times, mountains and trees have existed as objects of worship for people. The Okitama region is located inland in a mountainous area. To the south are the Azuma/Iide mountains, and to the north are the Asahi and Shirataka mountains. People and majestic mountains have always existed together. Hunting and gathering in the mountains, rivers, and forests, as well as resources collected from mining have supported the people for millennia. At the same time, the harsh nature and rugged terrain have at times taken lives resulting in reverence and fear of the natural world. Because of this, people have enclosed boulders and giant trees with shimenawa, given them divinity, and worshipped them for safety.

As if to connect the earth and the sky, trees are objects by which kami communicate with our world. They are also divine homes to spirits, and greatly outlive humans. The Okitama region has the foundation for worship such as mountain worship, tree worship, and animism, and you can see the spiritualism in the many somokuto in the area.

For the process of sending trees downstream and bringing them ashore, the people have to jump in the river, so prayers for keeping them safe during treacherous mountain work are made to the somokuto. If you look at the 34 somokuto built in the Edo period, 8 contain names of the village or area, 3 have religious association, 3 have individual names, 2 have names of priests, and 1 has the town name engraved. 17 having nothing engraved on them. It can be seen that in villages and settlements where they worshipped somokuto the unity of the mountain work organizations was strong.

Reverence, Gratitude, and Prayers Harbored in Somokuto

Thinking about the Coexistence of Nature and People’s Livelihood

The zaimokukyoyoto (1810) and zaimokukyoyoto (1866) in Fukuyama district in Shirataka aren’t counted toward the somokuto total count. However, it shares similarities to somokuto in that it shows appreciation towards the trees that we use and contains the prayers for growth. Kinemon Higuchi, who built the zaimokukuyouto (1866) was a sawyer. Yagoro, practitioner of the zaimokukuyoto (1810), worked in the mountains and did kinagashi.

The Izumine family in Ju-o district, Shirataka is a family that has continued their role as the yamamori for generations. An area in the mountains belong to the Uesugi territory. Izumine Sokichi built a somokukuyouyoto at the base of a pine tree at his home. Soukichi, who made a living logging, one day fell very ill. Soukichi, close to death, saw trees swirling around him as if he was looking though a kaleidoscope. Feeling as if he was being tormented by the many trees he had felled in his past, he erected a somokuto to calm the spirits of the trees. It is said he passed away soon after his parents heard of the somokuto.

The prayer “somokukokudoshikkaijobutsu” engraved in the early somokuto derives from the Buddhist idea that all living things can become a buddha in the Nirvana Sutra. It means, “even things that have no heart, such as vegetation and land, have Buddha-nature, so they all become Buddhas.” People and nature are in the same universe, and are closely tied with the natural world. The appreciation, prayers, and reverence that people in the mountains have for the mountains manifest in somokuto, and become one with nature. I hope to see the recapturing of the recognition we are in coexistence with nature through “somokuto” in the current changing of our outlook on the global environment and preservation of nature.